A silky detour at Nandi Hills

As we start our descent from Nandi Hills, I watch the fog move mysteriously around, hiding trees, flowers , birds , boulders in a sheath of white. The views of the sprawling townships around Bangalore are wrapped in its fold and are lost in the silky fabric. A puff throated babbler flies out of this thin white blanket and hides behind a thorny bush . It starts to sing and a couple of tawny bellied babblers join in the melody . We slowly reach downhill, following the curves of the road, but the fog disappears unveiling small pockets of villages .

We stop by at one such nondescript hamlet , living silently around the hills and stretch our limbs. The roads seem to lead nowhere . The only signs of civilization are a few humble homes scattered randomly in the landscape , a pack of street dogs having a noisy fight and a flock of chicken heading aimlessly, cluttering among themselves, exchanging perhaps gossip . We follow a lane that leads us to our destination- a small rudimentary shelter that offers the comfort of a simple house. Our host is Syed, who runs a small silk reeling unit, a livelihood that most families in nearby towns Doddballapur and Chikballapur still depend on .Syed has gone to the market, says Fauzia , who manages the unit in his absence. She carries with her a basket full of cocoons of the silkworms and throws them in a huge pan of hot water.

We leave our slippers outside and enter the dingy room. The windows are opened out , as smoke soon fills up inside the unit. My eyes get accustomed to the haze as I take a look around. Two women are working on the reeling units extracting silk from the cocoons , grappling with the heat on their faces. Baskets filled with silkworms and cocoons lie around . Inside the pan, the water boils as one of the women scoops the waste filaments out and flings them around inside another basket. Some wet filaments are hanging around the machines. “ We sell the waste and also the caterpillars locally to fisheries also , “ says Salma, as she joins her sister Fauzia and explains the routine to us.

Its an 8 hour shift for these women as they begin their day at 7 am. They buy the cocoons in large quantities from the local market and store it in their unit. Sometimes they purchase from the local society that acts as a bridge between units who are into sericulture. The farmers feed the caterpillars with mulberry leaves and wait for them to spin themselves into a cocoon. The cocoons are then sold to units who extract the silk from the harvested cocoons by a process called reeling.

Fauzia says “ We first cook the cocoon in the boiling water . “ This, she explains helps to soften a gum called sericin , that holds the silk filaments together in the cocoon. The fibres are then unwound to form a thread. She then asks one of the women to show the process to us. From the softened cooked cocoon the worker deftly removes thin strands of fibre and points to small button holes where the filaments are then wound on to a wheel through these button holes. A deafening noise fills the room as the machines start working on the filaments which are slowly removed together to form silk threads . This process is called the cottage basin method where multiple threads are then extracted from the cocoons to form silk everyday.

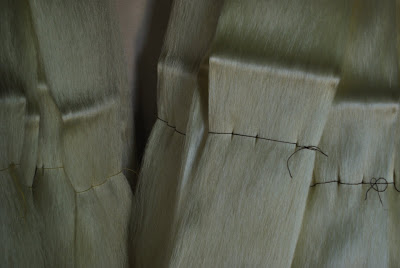

Fauzia shows me the creamy soft threads which are tied together and hung on the wall. The finished yarn is then hung on a nail and weighed and then sold to the market or to the local society. “ But there is very less money these days,” explains Salma as she takes out the weighing machine . Their profits are obviously dwindling by the day. What started as a fledgling industry by Tipu Sultan in Chennapatna and further developed by the Mysore Maharajas and Jamshedji Tata is probably just about surviving today.

Meanhwhile the kids return from school and pose for our camerasas one of the women gets up to leave. Tired with the heat around her, she is however amused by the attention that we give her. While I ask her about her work, all that she replies is “ Bahut salon se kar rahi hoon mein …(Ive been doing this for many years …) and breaks out laughing.

Its almost 3 pm and Fauzia gets busy with packing the yarn. We take one last look at the room and some of the cocoons still float in the hot water. It reminded me of the ancient Chinese myth that I had read about an Empress called Si Ling, also known as Goddess of the Silk worm. The legend goes that a cocoon fell into the princess’ cup of tea and it became silk when the hot liquid unwound it. The princess went on to become the patron goddess of the industry as well. As I step out, I realize that all I need now is a strong cup of tea .

This story was published in Spectrum, Deccan Herald a couple of days ago.

Did see this during my trip there.

Yes Indrani..the areas around Nandi Hills are filled with sericulture and silk reeling units

very interesting! but somehow, the thought of boiling the silkworms is a horrible thought! i remember reading about it in school and telling my mom I didnt want to wear silk! ever! Of course, i do wear silk sarees now, but think of it every time I do!

interesting and informative. My neighbour in Bangalore was in sericulture dept and he used to get the wasted cocoons(after removing thefilaments). We used to dye them in colors and make beautiful garlands.This was one of our pastime for me and my friends iln our childhood.

Fascinating..informative and interesting!!

but somehow boiling worms and making silk just doesnt go down well.. feel bad for the poor creatures…:(

hey very good article and interesting too..came to know many interesting facts from this.

Poor insects…:| But then what can we do,right?

I don’t feel like wearing silk anymore…not that I was very fond of it earlier. I like cotton best.